By Nini Gu

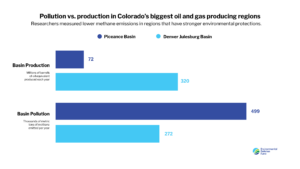

Data recently collected by EDF’s MethaneAIR project in 2023 reveals a striking difference in the emissions profiles between the two major Colorado basins: the Denver-Julesburg (D-J) in the east, and the Piceance in the west. The D-J Basin exhibited a 1.7% methane loss rate from the total natural gas produced; by contrast, the loss rate for the Piceance Basin hit 7%, a high figure among all surveyed basins.

In terms of total emissions, the Piceance Basin emitted 57,000 kg/hr of methane, close to double the emissions of the D-J Basin despite producing less than a third of the energy. Projected over a year the Piceance Basin emitted 499,320 metric tons of methane while producing around 77 million barrels of oil equivalent (BOE). The D-J produced much more energy than the Piceance (over 303 million BOE) but emitted only 271,560 metric tons of methane.

These differences likely have a number of causes, but their solution is clear – Colorado must accelerate efforts to reduce pollution statewide including in its current oil and gas air pollution rulemaking.

A Tale of Two Basins: Colorado regional oil and gas pollution differences highlight need for action on the West Slope Share on X

So why exactly is the Piceance Basin emitting so much more methane given its lower overall production and Colorado’s nation-leading rules? Answers may be found in the differences between their natural and regulatory landscapes.

The Piceance Basin is more mature, containing a significantly larger number of older, often lower-producing, wells that were drilled in the early 2000s, with drilling peaking in 2008. The older infrastructure at these so-called “marginal wells” tends to leak at a higher rate, contributing much more to the total loss rate of the Piceance Basin. Conversely, most oil and gas wells in the D-J Basin were spudded in the late 2010s, after Colorado adopted the first-ever state rule to directly regulate oil and gas methane emissions.

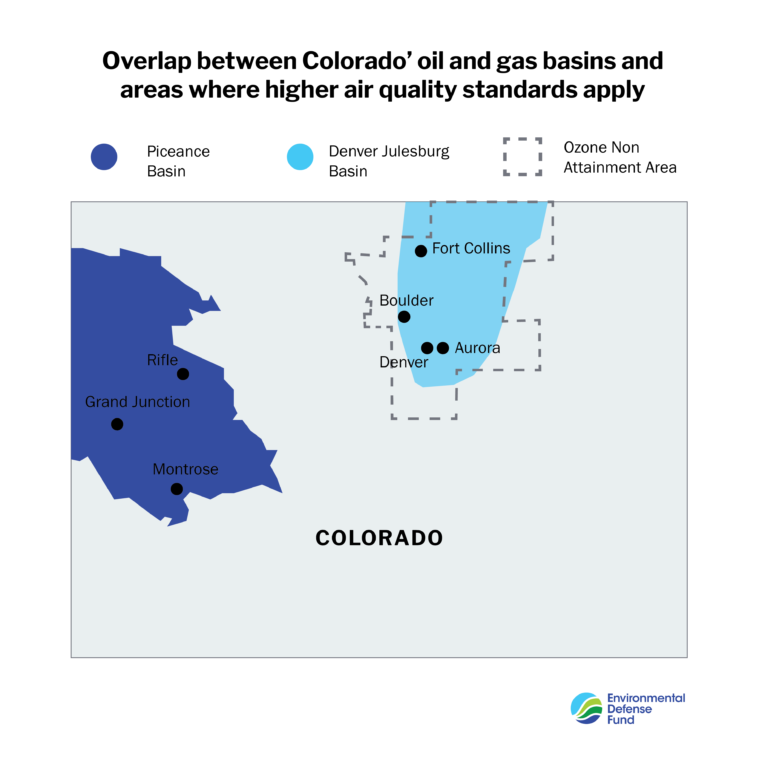

Additional regulations, especially those around ground-level ozone and zero-emitting pneumatic controllers in the D-J basin, have also likely affected emissions disparities.

Colorado has long struggled with ground-level ozone pollution, and in 2022, the US EPA downgraded the Denver Metro/North Front Range (DMNFR) area from “serious” to “severe” ozone nonattainment. These designations required the state to adopt more stringent regulations to reduce the emission of ozone precursors like volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Since VOCs are almost always emitted alongside methane during oil and gas activities, regulating VOCs in the D-J Basin reduces overall methane emissions as well.

In 2021, Colorado adopted a landmark rule that required operators to use non-emitting pneumatic controllers, covering both the installation of new controllers and retrofitting existing ones. Traditionally, pneumatic controllers – devices used to control valves that regulate process parameters like temperature and pressure – ran on natural gas, which meant methane and co-pollutants like VOCs were released every time a valve opened. Non-emitting alternatives run on compressed air or electricity instead (operators can also route emissions from natural gas-powered controllers to a combustor under the Colorado rule). However, this rule incentivized operators to retrofit the highest producing facilities first and exempted those who operate mostly low-producing, marginal wells. Moreover, the pneumatics rule required operators retrofit a certain percentage of existing emitting controllers based on the amount of total liquids production (oil and water) flowing through non-emitting controllers. This focus on high producing wells in basins with high liquids production directed the majority of retrofits to occur in the D-J Basin.

The state’s own emission inventory confirms the distinct impact of this rule on different regions in Colorado. The Air Pollution Control Division’s 2023 emissions inventory data shows that only 32% of pneumatic controller methane emissions occurred within the DMNFR ozone nonattainment area, which is the densest production region in Colorado’s D-J Basin; the majority of emissions originated from other areas (such as the Piceance Basin).

Between MethaneAIR and the state’s own data, it’s clear that regulators urgently need to tackle methane emissions across all sources in the Piceance and establish more regulatory parity between the basins.

Fortunately, the division is currently updating its requirements on pneumatic controllers, an opportunity to address this pollution gap for West Slope residents. But to do so it must accelerate its retrofit deadline of March 2029 to phase-in non-emitting pneumatic controllers for communities outside the ozone nonattainment area, which is currently two years slower than the deadline inside the nonattainment area. Given the serious impacts of methane pollution outside of the nonattainment area, the Commission should urge the Division to adopt an approach that is rapid, consistent, and prioritizes all communities statewide.

The Department of Energy is also expected to make final grant awards by the end of this year, including funding for marginal well operators to retrofit well sites with non-emitting pneumatic controllers. By adopting a shorter compliance timeline, it will incentivize operators to seek funds now that may be spent down and unavailable in future years.

Leadership isn’t just about doing things first—it’s about making sure that what you’ve done is working and continues to work. The Commission and Division have demonstrated a longstanding commitment to cutting emissions and policy innovation. They can build on that legacy here by improving their pneumatic retrofit requirements statewide to ensure that all Coloradans have a chance at a healthy life.